Etienne Gilson in God and Philosophy (1941) makes the argument that God’s existence can not be demonstrated, especially since the Church keeps embracing the God of Plato over against the Christian God of the Bible. Now, I know that I’ve heard this argument before. Usually it looks more like a pejorative point raised to defame ones opponents. So you’ll see the Open Theist pointing out that all of Christendom has inherited Plato’s Immutable Good as God instead of the relational God of Scripture. But that doesn’t seem to be the argument the author is making.

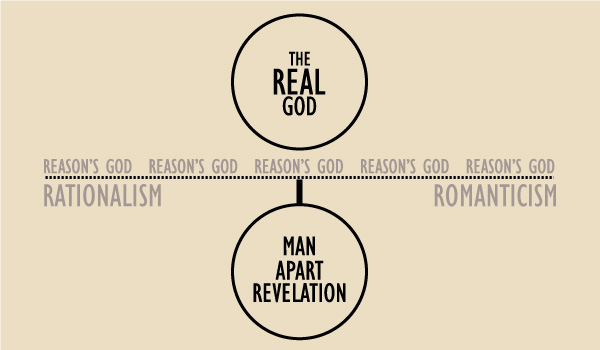

Etienne wants to show that the existence of the Christian God can’t be demonstrated philosophically because Human Reason bottoms out (or tops out). He starts off examining early philosophy and arriving at Plato’s conclusion: the furthest human reason can go is The Immutable Good. Philosophically speaking there’s not much reason to go further than what Plato came up with.

Christianity, though, stands against this having a God who is not only the Ultimate Good, or the First Cause, but he is intimately concerned with people, he creates, he pre-exists creation, he is personally involved, he incarnates—etc. Stuff that really can’t be established metaphysically.

Then the author looks at how Christians wound up doubling back on the God of Philosophy and calling him the God of the Bible. So you’ll have Augustine inheriting the world of Plato by falling “heir to Plato’s man” where man is not the “substantial unity of body and soul; he was essentially a soul.” Aquinas would be the crowning achievement of Natural Theology but then hits a glass ceiling where humans double back to human reason.

Descartes, using reason to establish that he exists and then using God to justify and trust his own reason: by doing this Descartes doubles back on the Philosopher’s God. He can assign a mess of categories to this God (that he incarnated, that he is personal, etc) but there’s no real reason to add all that. Etienne says that Descartes’ “philosophy was neither directly nor indirectly regulated by theology, he had no reason whatsoever to suppose that their conclusions would ultimately coincide. When you get to someone like Spinoza, labeled “an atheist by his adversaries”, we see a Non-Christian Cartesian who is a firm believer of his own Philosophical God while having nothing to do with the Christian God.

“God is the absolute essence whose intrinsic necessity makes necessary the being of all that is, so that he is absolutely all that is, just as, in as much as it is, all that is ‘necessarily involves the eternal and infinite essence of God.’”

I still haven’t finished the book (even if I enjoy watching a Tomistic Catholic anticipating Van Til), but it was interesting to think how these two categories can be seen in our own experience. You’ll have Christians defending a position because an idea comes forward as representing the entire Godhead though that idea is not established by Reason but Rationalism’s near sister: Romanticism.

Like the Philosopher’s God, Jesus winds up being this romanticized idea of Immutable Love who would never do such-and-such. This was really evident last week with the announcement on the death of Osama Bin Laden: Christians shouldn’t do X because Christ wouldn’t do that all based on a lot of wishful thinking and some proof-text. But if Plantinga (with his warranted Christian belief of Reformed Epistemology) and Calvin (with his sensus divinitatis)are right, it’s not really another God that folk are positing; it’s really just denying an aspect of The Real God which people don’t find appealing.

For instance, if the Gospel accounts didn’t include Christ clearing out the temple in anger, or getting ticked off at the wailing at Lazarus’ tomb, I have a feeling that people would say things like “Christ would never do that” because the romantic ideal is holding sway. They’d still be referring to the Real Christ but they’d be denying something he would do because it doesn’t coincide with their feeling of what Christ would do. It’s not a Cartesian God arriving at Plato, but something else. A God who is also not philosophically established as existent but persists because of a specific sub-cultural ideal.

Here’s some Carson from Love in Hard Places:

… to avoid distortion we should reflect on the love of God only in conjunction with reflection on all of God’s other perfections. Otherwise there will be a tendency to pit one attribute of God against other attributes of God, to domesticate one or more of God’s characteristics by appealing to the supremacy of another. If we rejoice in God’s love, we shall rejoice no less in God’s holiness, in God’s sovereignty, in God’s omniscience, and so forth, and we shall be certain that all of God’s perfections work together.

I think in both cases, it’s facing something CS Lewis warns about: you take Aslan on his own terms. He is no tame lion. Nor is he safe.